It’s nothing new for farmers to make tough decisions. And the nature of the business is such that those decisions are often informed by—and carry the weight of—generations of wisdom and stewardship.

Family is involved in decision-making. Again, nothing new. Adult children farm with their parents. Siblings farm together on family land. It’s the American way of farming.

But what if two prior generations of wisdom leave the farm suddenly, leaving a young farmer to move forward? And what if a remaining parent is, also suddenly, called upon to save that young farmer’s life?

Passing The Farm Down

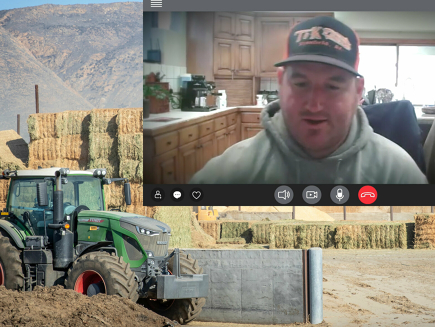

Raymond Davidson and his son, Mike, were full-share partners in Davidson Farm as the new century turned over in 2000. They were already the third and fourth generation on the family land, near Tioga, North Dakota. Mike’s son, Ryan, was still in high school at the time, but very much a part of the family business.

“I was active in the field from the time I was in first grade,” says Ryan, now the fifth generation. “I’d be picking rock, changing sweeps on cultivators, washing windows, you name it,” he says.

Raymond became very ill in 2001 and passed away in 2002. Ryan had just started college at nearby Williston State, but “I was already farming full-time,” he says. He had learned from the best. “He was his dad and grandpa’s shadow,” says Holly Wheeler, Ryan’s mom, who also helped on the farm, mostly working the books.

The fall of 2004, Holly says, was one of their worst. It was wet, it was cold; harvest approached and the crops weren’t mature. Then just two years after losing Raymond, the family lost Mike.

“My husband had an accident,” says Holly. “He didn’t survive.” From a business standpoint, Mike’s share of the farm turned over to Holly, but the day-to-day operations—and the decision-making—fell to Ryan.

The kid who had been in the field since First Grade was ready. “Ryan just didn’t take a second thought about stepping into those shoes,” says Holly.

“It was fairly natural,” says Ryan. Today, his home, where he lives with his wife, Jenice, son, Gavin, and daughter, Gracelyn, sits on ground that was homesteaded by his great, great grandfather in 1902. And he still farms the same land his ancestors farmed, but not without some changes—and some challenges.

Diversifying The Farm For Stewardship and Profit

Raymond and Mike had left the business in great shape, but they’d also passed down a legacy of stewardship that Ryan carries on and builds upon. “It was a pretty typical crop and summer fallow situation until the late ’80s,” says Ryan, when the farm went to continuous cropping in small grains. But disease pressure, especially in their durum wheat crop, meant it was time for change.

“Dad saw the door open in the mid ’90s to go into a more diverse rotation,” Ryan says, so they added some broadleaf crops. Eager to see some disease relief in the durum and to get a natural nitrogen boost in the soil, the Davidsons were among the first in the area to bring pulse crops—field peas, chickpeas, lentils—into their crop cycle.

Pulse crops were primarily planted further west, in the Palouse region of Washington state and Montana. In 1991, fewer than 2,000 acres were planted to field peas in North Dakota. By 2002, the year Ryan started farming full-time, North Dakota that acreage was up to more than 150,000.

It was profitable for North Dakota farmers by then, and remains an important cash crop for Ryan, besides the agronomic benefits to durum. Durum that follows a pulse crop can benefit from a nitrogen credit of up to 40 pounds per acre, a reduced risk for Fusarium head blight, and better soil moisture compared to other rotations. Pulse crops can even help increase protein content in the durum that follows, which impacts marketing grade.

Protein content also helps make pulse crops profitable, especially in today’s market. “It’s a high-quality protein on its own,” says Ryan. While he sees a good bit of his harvest go into feed for finishing cattle—“It produces a beautiful, marbled meat,” says Ryan—there’s an emerging consumer market for plant-based protein. “I’m not personally going to the grocery store and buying a plant-based burger,” Ryan laughs, but adds that the industries aren’t looking to pit one against the other and that there are distinct markets for both.

Ryan has brought along his own diversification, as well. While his father was already moving into broadleaf crops, Ryan saw an opportunity in sunflowers. Ten years ago, he says, he was growing around 80 acres; this year, black oil sunflowers will make up close to a third of his total 8,500 acres, much of it headed for the crusher or for commercial bird feed.

Good Neighbors With The Oil Industry

Farming in this part of North Dakota has an “added layer of complexity,” says Ryan. It’s a literal layer beneath the well-tended soil of Davidson Farm where, Ryan says, the landowner at the surface “has the least amount of rights.”

“We live right in the heart of the (Bakken) oil field,” says Ryan. He describes researching mineral rights for Davidson Farm through a book-length stack of pages at the county records office; “The mineral rights have been traded many times since my family homesteaded here,” he says. “The stuff that’s underground, they have the right to go get it, and they’ll get it whether you want to or not, so it’s a lot easier to work with them than try and work against them.”

Oil was discovered in North Dakota in 1951, but production doubled between 2004 and 2008—right at the time Ryan took over the farm. Traffic increased on the rural roads. The labor market became competitive. And the most crucial competition came in shipping, where oil and grain had to share the rails.

So when an opportunity came for Ryan to work with the Dakota Access Pipeline for a tank battery on his land, as well as having a part of the pipeline itself cross the property, he made the decision that benefitted his own farm and others in the region. “I know those pipelines are a sore subject,” he says, “but we’ve seen the other side of it.” Bakken oil is a light sweet crude, meaning it has a higher concentration of gas, and is more flammable. “It’s safer to transport it underground,” Ryan says, and it opens more capacity on the railroad for farm goods. “We need rail to ship our products,” he says. “We can’t put it in a pipeline.”

Carrying On A Legacy

“Things have progressed a whole lot since that time,” says Holly of the early 2000s when Ryan’s grandfather and father both passed. But it wasn’t the end of the challenges.

In 2014, “I had some issues… I started doctoring for it and found out I had a kidney disease,” says Ryan. He was placed on the transplant list in 2015, but the match didn’t take long, or come from far away. “My mom was the first one that got tested,” he says. “She was a perfect match.

“So she saved my life, and… here I am,” he says.

He admits he feels he has a lot to live up to. “I think daily about… What would Dad and Grandpa think? Would they be proud? And, I think they would…”

Holly, who describes her role now as “semi-retired,” says Ryan “has just done a wonderful job. I think he had some good teachers, and he’s got some good family background that’s done him well.”

“To me, legacy is the big driver of why I do this,” Ryan says. “This farm has been in the family for almost 120 years. They lived through the ’30s, the ’80s… they made it work. Am I doing good by them? It’s what I strive for every day.”

According to his mom, Ryan is absolutely bearing up under the weight of those generations. “The farm will be just fine,” says Holly, “because my son has been in charge of it for almost 20 years… it’s in good hands.”