“I’ve done the math,” says Michel Camps, reeling off the statistics for the business he built with his wife, Hanneke. Their CP Farms—near Barnwell, Alberta, in the heart of the province’s potato country—is responsible for “something like 12 million portions of fries each year. We can make a lot of fries out of an acre of potatoes,” he says, about 11,000 servings, based on an average 21-ton-per-acre yield.

Michel rolls through the numbers while standing on a mound of potatoes in a climate-controlled building that holds 6,000 tons of spuds at capacity. The entire farm can store some 24,000 tons. Meanwhile, Hanneke is hand-inspecting a 30-ton load of potatoes being moved via conveyor to a semi headed for processing. It’s one of a minimum of six loads per day, year-round. (Why the hand inspection? The machines can’t detect all the foreign matter in the load, “especially golf balls,” says Michel, which have the same density as a potato and wind up in their fields closest to town. “There are a lot of bad golfers in southern Alberta.”)

While Michel and Hanneke also farm sugar beets, corn, wheat and a little alfalfa, potatoes are the money crop. The Camps employ a one-in-four rotation for the potatoes, stricter than the processors require, but optimal, Michel believes, for soil health and crop quality. That means careful planning, calculating, math… to be successful with a high-input, high-risk crop.

But the math checks out, especially with three processors within 100 miles of the farm, waiting to ship fries to customers from the Rockies to the West Coast and even Asia. Ninety percent of CP Farms’ Russet Burbank potatoes wind up in fast food restaurants; CP Farms alone could “keep Los Angeles supplied with fries for a few days,” laughs Michel.

Their story, like that of any successful business, involves some calculated risk, too. “I don’t think, in the farming industry, that it pays to be stubborn,” says Michel; he believes a willingness to adapt is something that sets CP Farms apart. That has been true from the start.

“We’re leaning a little heavy into the romance stuff,” jokes Michel, as he and Hanneke smile for photos in the front yard of their farmhouse. It’s just steps from the original storage facility and the 250 acres they bought as newlyweds in 2002. Michel says the beginning of their partnership “wasn’t very romantic.”

“We were working in a chicken barn, loading poultry,” says Hanneke of the jobs they both held as teens in their native Netherlands. “That’s where we met.”

“It involved being chased by chickens, coming home with scratched hands, you’re tired, you stink… It’s not how typical people would have a date,” says Michel, but he notes how good Hanneke was at the job; faster than him, in fact. “And that really annoyed me,” he laughs. “I thought to myself, ‘I’ve got to hang on to this one.’”

Both had an education in animal ag, both were farm kids, both had interest in farming, but land prices in the homeland were prohibitive. Meanwhile, southern Alberta was something of a hot spot for Dutch immigrants, with young Netherlanders steeped in the potato business “following the money,” Michel says, to the area when potato processors got established in the late 1990s. He and Hanneke wanted work experience abroad and were part of the “first wave” of mass Dutch emigration. And while their backgrounds were in livestock, the prospect for potatoes was hard to ignore.

Hanneke remembers the first time she saw their farm, which they bought from an elderly potato farmer who was coincidentally looking for a younger farmer to take over. “It was a big… opportunity,” she says, smiling, acknowledging that the place was “a mess… and we didn’t have a lot of money. But we had two hands.”

“All of a sudden, we were in the potato business,” says Michel. “It proved to be a golden move.”

The Camps are part of a potato boom in southern Alberta. Today, United Potato Growers of Canada statistics show the province is set to surpass Prince Edward Island and Manitoba as Canada’s top producer, both in raw tonnage (a 132% increase over the past two decades) and yield (382 cwt, or about 21.4 tons, per acre, the leader in 2019).

Michel and Hanneke kept up by expanding their land holdings almost ten-fold since 2002; they own 2,200 acres and farm another 1,000 by renting and sharing with other farmers, which helps with their demanding one-in-four rotation pattern. While Michel says they have no regrets, he does wish they’d been more aggressive in the land market early on. “Land values have risen 400% in the time we’ve been here,” he says. “We should have bought every piece of land we could.”

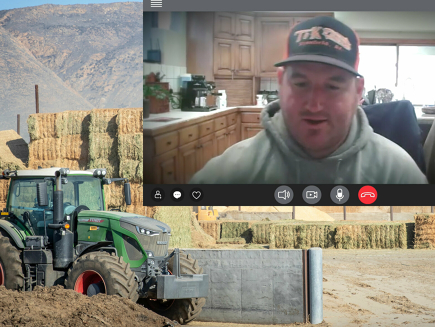

One opportunity the Camps haven’t missed is adapting to the latest in tractor technology, which has even pushed Michel to invent new equipment to take advantage of upgrades.

The Camps’ 517hp Fendt 1050 led to one such innovation at planting. On the front of the tractor are two 450 gallon tanks, one fertilizer and one fungicide. Directly behind the tractor is a rototiller that requires 350hp alone. Behind that is an 8-row planter that Michel modified in his shop with a gooseneck so all the equipment could run simultaneously. “So when that machine is done,” he says, “we’re finished.”

The math definitely checked out on that. Combining those operations into one pass “saved on operator costs, saved on fuel costs, saved on ownership costs,” he says. “$7 an acre, which on 1300 of potatoes is a significant number, and that’s on the planting side alone.”

Weather plagued their 2019 potato crop, which doesn’t make the Camps unique among any farmers in North America last year. But the circumstances were unusual. Last August, in the space of 15 minutes, hail took out the topside foliage on two-thirds of the potato crop, which in turn stops the flow of nutrients to the tubers below the surface. The quality loss at that point isn’t recoverable. “It cut our season 40 days short, so you have immature tubers that have low starch content,” says Michel. “You can’t make fries out of water.”

Weather worries Michel the most, he says, because it’s the one thing he can’t control. But while the Camps also face the mathematical reality of ever-rising input costs against level consumer prices, that’s an equation they can balance with innovation. Building a new piece of equipment to work with an efficient tractor is only one example.

“We push yields,” he says. “We improve our planting strategy, our fertility management… we get better at what we do.”

It works. They’ve done the math.

Story by Jamie Cole