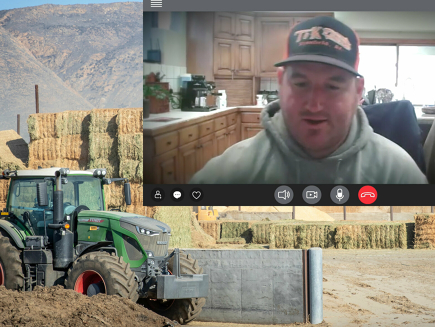

Here on the rolling red plains of northwest Oklahoma, there isn’t much to stop the seemingly constant wind as it sweeps across the open vista. Dotted by far-flung farmhouses and clusters of towering wind turbines, the scene is stark yet stunning, desolate yet dramatic.

Danny Floyd’s cows don’t seem to notice the winds or the view, however. They’re more intent on grazing the expanse of pasture before them. And while Floyd often finds himself in awe of the landscape, it’s his enthusiasm for the cattle in his care that is most evident on this autumn afternoon.

For more than 35 years, Floyd has run Floyd Farms, a cow/calf operation just outside Thomas, Oklahoma. Located about 90 miles northwest of Oklahoma City, the area is settled by those who make a living in agriculture and energy. Floyd has done both. He started a company that produces chemicals for the oil and gas industry, but he’d rather spend a day with his cows.

“When we bring the cattle in to work the cows and work the calves, I enjoy that a lot,” he says. “The Lord has been good to me. He’s blessed me in more ways than I ever deserved.”

When Cattle Call

Floyd and his wife, Linda, married in 1981. They purchased their first piece of property, a 40-acre plot, with plans to raise sheep. However, tending the flock in Custer County turned out to be a trickier proposition than Floyd envisioned.

“I figured out quick the coyotes did better on the sheep than I did,” he recalls with a reluctant shrug. When the 160-acre quarter section next to his 40 acres came up for sale, he bought it and began the switch to cattle. “When I was young, my father had a cow/calf operation in Seminole County, so I grew up around cows.

“I have many friends who are bankers, and as I listened to them, it became very clear to me that the cow/calf operators had very little debt,” he explains. “They made more money consistently on a year-end basis, and I felt like cow/calf would fit here. It’s worked well for us.”

As opportunities to expand onto neighboring acreage presented themselves, Floyd purchased more land and added more cattle. What began modestly with 200 acres and a few dozen head has become an operation encompassing more than 8,500 acres across both Custer and Dewey counties. Today, Floyd runs roughly 1,200 mama cows on those acres.

Producing Pounds Of Beef

Floyd primarily raises Beefmaster cattle, a breed developed in the early 1930s and officially recognized by USDA in 1954. Tom Lasater, the breed’s founder, systematically crossed Herefords, Shorthorns and Brahmans to create cattle that would flourish in hot, dry conditions. Those traits serve the breed well in northwest Oklahoma, Floyd attests.

“We’re just about raising pounds of beef,” he says. “We primarily run Beefmaster bulls because we found that they have better gains than traditional British breeds, such as Angus and Hereford. Not knocking those breeds—they’re very good breeds—but the Beefmaster was bred for beef. They’ll gain at least 75 pounds, sometimes up to 100 pounds more per calf than the Angus or Herefords.”

While many cattlemen manage their herds for seasonal breeding—producing crops of calves in the spring or fall—Floyd opts for a year-round breeding program. He leaves his bulls in with the herd all the time, instead of only putting a bull with receptive cows for a limited period.

“By doing so, we feel like we gain a calf per cow. If a cow can have one more calf, that’s another 1,000 pounds of beef,” he says. “We also have different times that we have a cash crop [calves] to sell. We don’t always have to wait a year to get one cash crop.”

Grazing Gains

To fatten those Beefmaster calves, Floyd primarily runs his herds on pastures planted seasonally to mixtures of cereal grains, grasses and legumes, though he also feeds hay during winter months. While some producers may graze cattle on such crops, only to pull the cows off in the spring and allow the crop to go to grain, Floyd doesn’t subscribe to this dual-purpose approach.

“We don’t harvest any grain at all. Everything goes through our cows,” he explains. “We feel like we make more money that way than we do harvesting the grain.”

Each spring, the 3,600 tillable acres of Floyd Farms are planted to a cover-crop mixture that includes warm-season plants such sudangrass, millet and cowpeas. The pastures are grazed through the summer and into the fall, when Floyd plants a winter pasture mixture of rye, triticale, wheat and barley.

“These plants all respond differently at different times, so we have better pasture during the winter months,” he says. “We can gain anywhere from 2.5 to 3.5 pounds per day per steer on winter pasture.”

Future Focus

While Floyd and Linda may have been the ones to start Floyd Farms, they are by no means the only family members involved. Both a son and a son-in-law are employed in the cow/calf operation today, as are Floyd’s sister, a nephew and two grandsons. Together, they have a vision for what the farm

can become.

“I hope to have up to 5,000 mother cows in the near future,” Floyd says. “As we grow this, I may put in my own feedlot and then try to market my own. If you have control from cradle to grave, at that point, you get to control the pricing a lot more. You get to control your profitability.”

After surviving a health scare eight years ago, Floyd put a plan in place to ensure the farm will endure for at least three generations. “That’s as far as Oklahoma law will let you,” he adds.

With four children, 10 grandchildren, one great-grandson and a marriage of 38 years, Floyd says family far outweighs any other accomplishment in his life. He counts his blessings daily.

“I feel like I have a pretty vanilla life, but I just work and try to make things better,” he says. “The day you leave this earth, the day before should have been your best day, the most memorable day.”

Story by Jason Jenkins