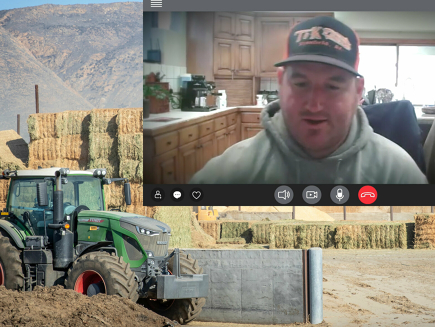

Matt Barnard’s friends and family like to say that he’s thinking ahead, unique, “farming differently,” says Kelly Duzan, who supports the Barnard Farms Partnership with Fendt equipment and service. “He’s not in the ‘safe zone’ of farming… he’s not, ‘I’ve always done it this way,’” he says.

Being outside the “safe zone” of farming doesn’t mean the Barnards take wild risks; quite the opposite. An entrepreneurial spirit drives Barnard Farms Partnerships to new paths for progress, as well as new ideas related to but separate from farming itself.

The family operation, which includes Matt’s father, Ted, and brother, Brett, along with their spouses, spans six counties and takes a unique approach both to funding growth and farming the ground. By inviting a group of investors to fund land purchases, the family partnership has expanded to several thousand acres, and offers investors positive returns by careful use and review of data to maximize return, if not necessarily yield.

“We really look at dollars per acre versus bushels per acre,” says Barnard. “Sometimes, you can make more money raising 200-bushel corn than you can 240 or 260.” As Matt told FarmLife in 2019 (see the full story here), the Barnards might, for instance, select a corn hybrid for a field with poorly drained soil based on that hybrid’s nitrogen-use efficiency, rather than overall yield.

“If we know we’ve got ground that’s not as receptive to high volumes of nitrogen, we’ll look to plant corn hybrids that are really efficient,” Barnard said in 2019. “Instead of using 1.2 pounds of nitrogen to make a bushel, maybe they use 0.7 or 0.6 pounds.”

Today, data still play a significant role in the Barnards’ overall farming strategy, but they have found a way for the family and other farmers to further monetize the volumes of information they’re already collecting for other purposes.

Data Driving Business Beyond Farming

“Have you ever been doing something on Facebook or Amazon, and all of a sudden you get something in your feed about something you talked about and you wondered why that happened?” Barnard asks. “It's the data that's being pulled from your history and it’s being used to market to you. And we were thinking that that probably could happen in ag.”

As he described before, data sets are already prescriptive for hundreds of thousands of other farmers, but there is still benefit to be mined from data beyond selecting hybrids and prescribing inputs. “So Verdova was started,” says Barnard. “And it’s since now grown over 10 million acres with growers in 20 plus states that are allowing us to be the stewards of their information.” The company (based online at verdova.com) cleans and unifies data that farms are already collecting and markets it to companies willing to pay for it, with the farmer getting an 80% share on the sale.

And the benefit goes beyond the money. As Barnard describes, that data will help interested parties “better understand you as a customer, better understand maybe products that would fit or help unlock different programs, like sustainability, that you might be a fit for that you didn't even recognize,” he says. Farmers can join Verdova for free.

“As AI continues to evolve and as the technology continues to improve, we're able to capture so much more stuff,” he says. “And the things that you and I might think mundane, like the amount of usage of diesel fuel per acre, that's all of a sudden a really big deal for somebody that's trying to do something sustainable.”

Fuel use per acre has become a “really big deal” indeed as the Barnards convert their tractor fleet to Fendt. “Because (of) the use and the efficiency of a Fendt tractor, and only using 13 or 14 gallons an hour running at 1400 RPMs, I am a sustainably friendlier alternative than maybe my neighbor,” Barnard says. “And now all of a sudden, I've turned my just traditional corn and soybean operation into a specialty crop with only collecting the information from my Fendt machinery to do so.”

Fendt Is A Total Management Solution

The efficiency of the family’s first Fendt tractor, purchased in 2019, led to a progressive fleet conversion that continues to pay off. “It was proposed to us about something that was super efficient, super reliable, very easy to use,” Barnard says of the Fendt line. “(And we) started to say, ‘Hey, we need to explore other opportunities.’ So we bought a Momentum planter. And it was ahead of its time and it’s allowed us to be more efficient and productive and it’s got features that are unique to the industry,” he says. “And then jumped into the IDEAL combine side of things. And then went from one Fendt tractor to four,” he adds.

“We have to try and be better at what we do, and Fendt fits that,” he says. That started with realizing the full potential of the Fendt 1000 series of tractors. “I completely underestimated the versatility of a 500 horsepower front wheel assist tractor,” he says. “So we always thought about it as being a row crop tractor, a planter tractor. But we’ve bought one now that we've just replaced a four-wheel drive, 600 horsepower tractor.”

Duzan, who helped the Barnards build their Fendt fleet, says a demo helped the family see the potential of Fendt for every job. “He put a 500-horse Fendt 1050 on the same tool that the big 575 was running,” says Duzan. “Not only did it do the job with ease, but it also was running 2 miles per hour faster and burning 10 gallons less an hour.”

The Momentum planter increased planting speed and accuracy, especially on rolling land in some of the Barnards’ more remote farms. “The ability for that planter to plant fast, transfer its weight, but also go through a lot of different uneven elevations out in the field is a big deal,” Barnard says.

The IDEAL combine is “a completely different thing,” says Barnard. “Combining, for the first time in my life, has been fun. I actually just let the IDEAL harvest do its thing and it made clean samples and adjusted itself and it was really easy.” The Barnards will add a second IDEAL combine to the fleet this fall.

While the Barnards are impressed with how the machines perform individually, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. “So many people that I see get a Fendt tractor, the first thing I say to them is, ‘You’re going to get a planter, you’re going to get a combine, you’re going to get another one,’” Barnard laughs.

Why? Duzan explains Barnards’ fleet change as a complete management solution. Besides the speed and efficiency of the tractors, the farmer gets speed and accuracy from the Momentum planter, which means better, more consistent stands at harvest time. Then the IDEAL combine improves the grain sample while providing more capacity overall, faster unloading, and better residue management, “which is then tying back into spring planting season,” says Duzan. Full circle, full benefit.

“Quite honestly, Fendt is the only place where you’re going to find that,” says Barnard. Add the Fendt Gold Star warranty and the management solution is complete. “Knowing what that fixed cost is and knowing that we actually can push our equipment a little bit further than what we thought we could a combine or thought we could tractor or thought we could planter, it makes that net cost of our machinery number and that machine repair number a lot more manageable,” he says.

“And we are looking very much forward to what Fendt is going to bring in the future. They seem to constantly innovate and push that bar a little bit further. We've been spoiled and are starting to expect that,” Barnard says. “I think that we feel very confident we’re at the right spot to get us to wherever tomorrow’s going to be.”

Story by Jamie Cole